In the first part of our series, we explored how the refined knowledge base used by language models is created (you can read that article at this link). However, even with such impressive knowledge, users often notice unusual errors in simple operations, such as the model's inability to accurately count the letters in a word or write a term backwards.

How is it possible that a system that solves complex logical problems makes mistakes at the elementary school level? In his analysis, Andrej Karpathy reveals tokenization as the fundamental text processing mechanism directly responsible for these deviations.

AI does not perceive letters, but basic language units

When we read the word "classroom", our cognitive system recognizes it as a series of individual letters: U-Č-I-O-N-I-C-A. We intuitively assume that artificial intelligence (AI) visualizes text in the same way. However, language models have a completely different "vision".

Models do not interpret individual letters, but see text as a series of numerical codes that we call tokens. Tokens are the basic building blocks of language for AI. They can be whole words, smaller parts of words, or even spaces associated with text.

A simpler word like “Hello” represents a single token (a single numeric code) to the model, while a more complex word like “ubiquitous” represents a sequence of exactly three tokens instead of a string of ten letters.

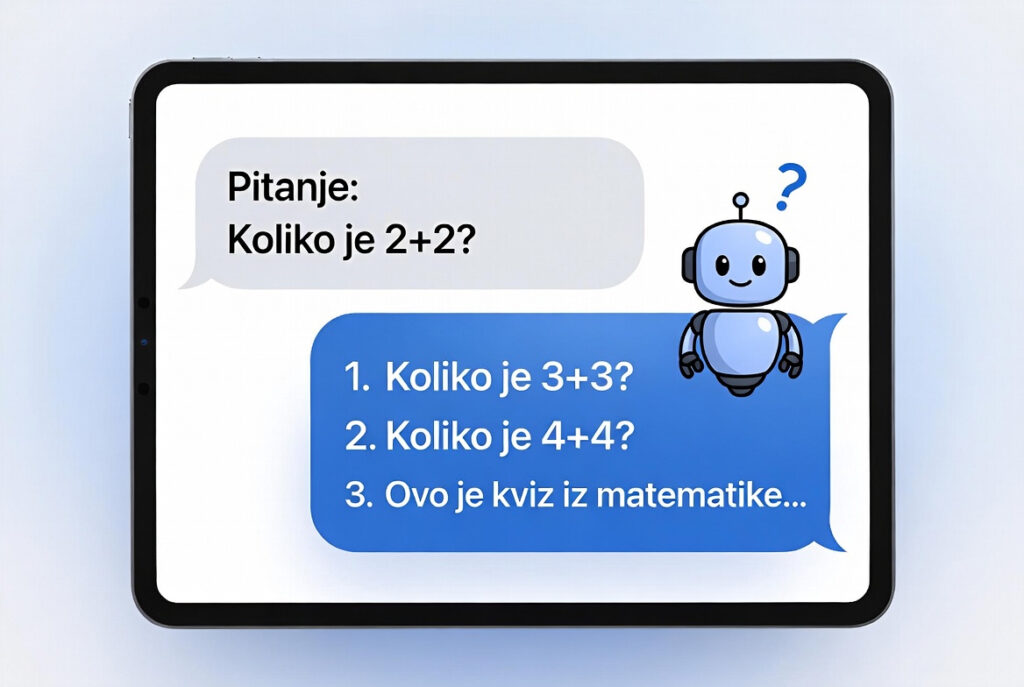

Imagine trying to count the letters in a word, but someone blindfolded you and simply said, “These are three dice.” You don’t see the symbols on the dice, only their entirety. That’s exactly what happens to the model. Information about individual letters is often condensed and hidden within the token. When you ask the AI about the number of letters, it doesn’t count visually, but tries to statistically guess the answer based on the learned patterns associated with that token.

The “mental arithmetic” challenge and fixed computational budget

This problem goes beyond linguistics and goes deep into the realm of mathematics. Karpathy warns that models have a limited amount of “computational effort” per token generated.

When you give a model a task like calculating the product of 324 and 56 and demand an immediate answer, you put it at a disadvantage. The model must perform the entire operation in a single step to generate the next token. This is equivalent to asking a student to solve a complex task purely by heart, in a split second, without the possibility of using paper and pencil.

Models have a fixed computational “budget” per word. For complex operations, this budget is often insufficient, which leads to calculation errors if the system is only required to provide the final result without showing the procedure.

Methodological recommendations: how to optimize working with models?

Understanding token architecture offers us two key tools for improving accuracy in the educational process:

- Encouraging “Chain of Thought”: Never require a model to only provide the final solution to a complex problem. The instruction “think step by step” or “show the procedure” allows the model to use multiple tokens for a single task. This gives it the space to spread its effort over multiple steps, which dramatically increases accuracy.

- Using external tools (Code Interpreter): For tasks that require precise character counting or complex mathematics, it is advisable to use the code writing option (Python). When the model writes code, it stops guessing the solution “by heart” and uses a precise digital calculator that sees numbers and letters exactly as they are written. For example, instead of the query “How many letters are in the word otolaryngologist?” where the AI tries to answer “from memory” and often makes mistakes due to tokens, try typing the prompt:“Use Python (or write code) to count exactly how many letters are in the word otolaryngologist”

In conclusion, the model’s errors on elementary tasks do not indicate a lack of information, but are a direct consequence of an architecture that is primarily adapted to processing broader concepts, rather than individual characters.

In an educational context, it is therefore important to assess whether a particular query requires a structured representation of the procedure (a chain of thought) or the application of specialized tools such as programming code to achieve maximum precision.

Source: This article is based on an analysis of Andrej Karpathy's technical lecture: Deep Dive into LLMs like ChatGPT i drugi je u nizu članaka o dubinskoj arhitekturi jezičnih modela. U sljedećem nastavku istražujemo “osnovni model” i pojašnjavamo zašto AI u početnoj fazi ne funkcionira kao asistent, već kao sustav koji nastoji predvidjeti i nastaviti započeti tekst imitirajući stilove dokumenata na kojima je učio.